MAIN PUBLICATION :

| Home � ECONOMICS � Project Financing � Recent developments |

|

Recent Developments

STRUCTURED FINANCE

The last five years has seen the emergence of a number of new forms of transaction for wind financing, including public and private bond or share issues. Much of the interest in such structures has been with renewable energy funds, long-term investors, such as pension funds, and even high net worth individuals seeking efficient investment vehicles. The principle behind a structured finance product is similar to that of a loan, being the investment of cash in return for interest payment; however, the structures are generally more varied than project finance loans. As a result, there have been a number of relatively short-term investments offered in the market, which have been useful products for project owners considering project refinancing after a few years of operation. Structured finance investors have had a considerable appetite for cross-border deals and have had a significant effect on liquidity for wind (and other renewable energy) projects.

BALANCE SHEET FINANCING

The wind industry is becoming a utility industry in which the major utilities are increasingly playing a big role. As a result, and while there are still many small projects being developed and financed, an increasing number are being built 'on balance sheet' (i.e. with the utility’s cash). Such an approach removes the need for a construction loan and the financing consists of a term loan only.

PORTFOLIO FINANCING

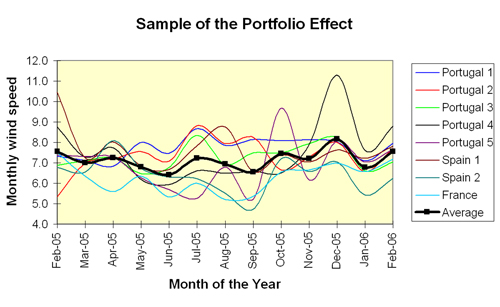

The arrival of balance sheet financing by the utilities naturally creates “portfolio financing,” for which banks are asked to finance a portfolio of wind farms rather than a single one. These farms are often operational and so data is available to allow for a far more accurate projection of production. The portfolio will usually include a range of projects separated by significant physical distances, with a range of turbine types. The use of different turbine types reduces the risk of widespread, or at least simultaneous, design faults, and the geographical spread 'evens out the wind'. It is possible to undertake a rigorous estimation of the way in which the geographical spread reduces fluctuations (Marco et al. 2007). Figure 3.2 shows the averaging effect of a portfolio of eight wind power plants in three countries.

Figure 3.2: The Geographical Portfolio Effect

Source: Marco et al. 2007

Finally, if the wind farms are in different countries then the portfolio also reduces regulatory risks.

The risk associated with such financing is significantly lower than that of financing a single wind farm before construction and attracts more favourable terms. As a result, the interest in such financing is growing. Portfolio financing can be adopted even after the initial financing has been in place for some time. It is now quite common to see an owner collecting together a number of individually financed projects and re-financing them as a portfolio.

TECHNOLOGY RISK

The present 'sellers’ market', characterised by the shortage in supply of wind turbines, has introduced a number of new turbine manufacturers, many of which are not financially strong and none of which has a substantial track record. Therefore, technology risk remains a concern for the banks, and the old-fashioned way of mitigating these risks, through extended warranties, is resisted forcefully by new and experienced manufacturers. So technology risk has increased recently, rather than diminishing over time. However, some banks still show significant interest in lending to projects that use technology with relatively little operational experience.

OFFSHORE WIND

Offshore wind farms are now more common in Europe. The first few projects were financed in the way described above - by large companies with substantial financial clout, using their own funds. The initial involvement of banks was in the portfolio financing of a collection of assets, one of which was an offshore wind farm. Banks were concerned about the additional risks associated with an offshore development, and this approach allowed the risks to be diluted somewhat.

Although there are still relatively few offshore wind farms, banks are clearly interested in both term loans, associated with the operational phase of offshore wind farms, and the provision of construction finance. This clearly demonstrates the banks’ appetite for wind energy lending. It is too early to define typical offshore financing, but it is likely to be more expensive than that for the equivalent onshore farm, at least until the banks gain greater confidence in the technology. The risk of poor availability as a result of poor accessibility is a particular concern.

BIG PROJECTS

Banks like big projects. The cost of the banks’ own efforts and due diligence does not change significantly with the project (loan) size, so big projects are more attractive to them than smaller ones. Wind projects are only now starting to be big enough to interest some banks, so as project size increases, the banking community available to support the projects will grow. Furthermore, increasing project size brings more substantial sponsors, which is also reassuring for banks.

CONCLUSIONS

The nature of wind energy deals is changing. Although many small, privately-owned projects remain, there has been a substantial shift towards bigger, utility-owned projects. This change brings new money to the industry, reduces dependence on banks for initial funding and brings strong sponsors.

Projects are growing and large-scale offshore activity is increasing. Since banks favour larger projects, this is a very positive change. If the general economic picture deteriorates, this may give rise to certain misgivings concerning project finance, in comparison to the last few years, but political and environmental support for renewable energy means that the funding of wind energy remains a very attractive proposition. Obtaining financing for the large-scale expansion of the industry will not be a problem.

| Acknowledgements | Sitemap | Partners | Disclaimer | Contact | ||

|

coordinated by  |

supported by  |

The sole responsibility for the content of this webpage lies with the authors. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Communities. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that maybe made of the information contained therein. |